Better than Round 1, but still missed by several hundred. If I had been able to get a second problem complete, I think I could have advanced. However, my attempt at the third problem turned out to be way too slow.

There is one edge case to concern ourselves with... if we are a mote of size 1, then it isn't possible for our mote to absorb anyone. In this case, we have to return that we remove all remaining motes, as our strategy for comparison would go into an infinite loop.

Another concern is the runtime. Fortunately, our recursion only needs to run down a single branch for each decision, since if we have to remove motes, we know we have to remove all of them. With that in mind, we run in O(N) time with respect to the length of the mote list... The other concern is when the next remaining mote >> our current mote. But by picking the largest mote available to absorb, we nearly double in size with each iteration, which means we can cover the gap in O(log(M)) time, where M is with respect to the maximum size of a mote. So our algorithm is something like O( N log(M) ).

So if we sum all those layers together, we get...

Where D is the number of diamonds, and L is the layer of interest. So given that that previous layer must be complete before we start our own layer, we can subtract away everything from the layer below our own, and are left with N-D diamonds.

Now I'd reform the question as follows... how many of the remaining diamonds would have to fall on the opposite side from ours for the layer not to complete up to our location? Well, our location at height Y means that there would have to be at least Y diamonds falling on our side for us to get a diamond. That means that if only Y-1 diamonds fell to our side, N-D-(Y-1) diamonds must fall to the other side. If this number is greater than the other side can hold, then there is a 100% chance that our location will get a diamond. If N-D < Y-1, then there is a 0% chance that our location will get a diamond.

A quick google search tells me...

"

Since the probability p = 0.5 (its equally likely to fall left or right), and we want to consider all cases from Y to N-D, we can reformulate as follows...

So we've arrived at a formula for calculating the probability. I haven't checked my numbers, since I didn't actually reach this part in competition, but I'm fairly certain that it will work. Another optimization in implementing this summation is to recognize that as w gets larger, the added probability gets smaller. We probably can stop the search early if the probability of the last iteration times the remaining iterations is less than the threshold google checks for... In cases where N-D is quite large relative to Y, this can be very useful.

Problem Osmos:

Armin is playing Osmos, a physics-based puzzle game developed by Hemisphere Games. In this game, he plays a "mote", moving around and absorbing smaller motes.

A "mote" in English is a small particle. In this game, it's a thing that absorbs (or is absorbed by) other things! The game in this problem has a similar idea to Osmos, but does not assume you have played the game.

When Armin's mote absorbs a smaller mote, his mote becomes bigger by the smaller mote's size. Now that it's bigger, it might be able to absorb even more motes. For example: suppose Armin's mote has size 10, and there are other motes of sizes 9, 13 and 19. At the start, Armin's mote can only absorb the mote of size 9. When it absorbs that, it will have size 19. Then it can only absorb the mote of size 13. When it absorbs that, it'll have size 32. Now Armin's mote can absorb the last mote.

Note that Armin's mote can absorb another mote if and only if the other mote is smaller. If the other mote is the same size as his, his mote can't absorb it.

You are responsible for the program that creates motes for Armin to absorb. The program has already created some motes, of various sizes, and has created Armin's mote. Unfortunately, given his mote's size and the list of other motes, it's possible that there's no way for Armin's mote to absorb them all.

You want to fix that. There are two kinds of operations you can perform, in any order, any number of times: you can add a mote of any positive integer size to the game, or you can remove any one of the existing motes. What is the minimum number of times you can perform those operations in order to make it possible for Armin's mote to absorb every other mote?

For example, suppose Armin's mote is of size 10 and the other motes are of sizes [9, 20, 25, 100]. This game isn't currently solvable, but by adding a mote of size 3 and removing the mote of size 100, you can make it solvable in only 2 operations. The answer here is 2.

My Solution:

This is actually a pretty easy problem, both for the small and large sets. The strategy in Osmos should always be just absorb the smallest remaining mote, if you can. Once you can't absorb the smallest, you can't absorb any other ones, so it is up to us to either add a new mote which you can absorb, or remove all the remaining motes. Since we have a vested interest in seeing you absorb the motes with as little help as possible, we want to give you the biggest mote you can currently absorb. This lends itself well to a recursive solution, where you have your current size, and a sorted list of the remaining motes.

There is one edge case to concern ourselves with... if we are a mote of size 1, then it isn't possible for our mote to absorb anyone. In this case, we have to return that we remove all remaining motes, as our strategy for comparison would go into an infinite loop.

Another concern is the runtime. Fortunately, our recursion only needs to run down a single branch for each decision, since if we have to remove motes, we know we have to remove all of them. With that in mind, we run in O(N) time with respect to the length of the mote list... The other concern is when the next remaining mote >> our current mote. But by picking the largest mote available to absorb, we nearly double in size with each iteration, which means we can cover the gap in O(log(M)) time, where M is with respect to the maximum size of a mote. So our algorithm is something like O( N log(M) ).

Problem Falling Diamonds:

Diamonds are falling from the sky. People are now buying up locations where the diamonds can land, just to own a diamond if one does land there. You have been offered one such place, and want to know whether it is a good deal.

Diamonds are shaped like, you guessed it, diamonds: they are squares with vertices (X-1, Y), (X, Y+1), (X+1, Y) and (X, Y-1) for some X, Y which we call the center of the diamond. All the diamonds are always in the X-Y plane. X is the horizontal direction, Y is the vertical direction. The ground is at Y=0, and positive Y coordinates are above the ground.

The diamonds fall one at a time along the Y axis. This means that they start at (0, Y) with Y very large, and fall vertically down, until they hit either the ground or another diamond.

When a diamond hits the ground, it falls until it is buried into the ground up to its center, and then stops moving. This effectively means that all diamonds stop falling or sliding if their center reaches Y=0.

When a diamond hits another diamond, vertex to vertex, it can start sliding down, without turning, in one of the two possible directions: down and left, or down and right. If there is no diamond immediately blocking either of the sides, it slides left or right with equal probability. If there is a diamond blocking one of the sides, the falling diamond will slide to the other side until it is blocked by another diamond, or becomes buried in the ground. If there are diamonds blocking the paths to the left and to the right, the diamond just stops.

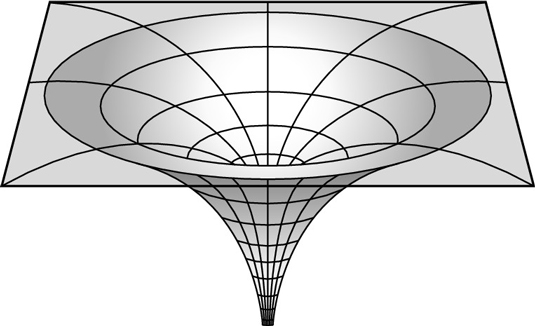

Consider the example in the picture. The first diamond hits the ground and stops when halfway buried, with its center at (0, 0). The second diamond may slide either to the left or to the right with equal probability. Here, it happened to go left. It stops buried in the ground next to the first diamond, at (-2, 0). The third diamond will also hit the first one. Then it will either randomly slide to the right and stop in the ground, or slide to the left, and stop between and above the two already-placed diamonds. It again happened to go left, so it stopped at (-1, 1). The fourth diamond has no choice: it will slide right, and stop in the ground at (2, 0).

My Solution:

So I didn't reach the problem until after the contest had ended, but I was I had. There are a couple of insights that make this problem much easier to solve than the third problem. First, you may notice that what we are making is a pyramid, one layer at a time. Each layer of the pyramid (centered at 0,0) is completed before the next layer can begin, because we need the peak of the pyramid in place before a diamond can slide out to the next tier.

So how many diamonds are in a tier? Well, we can inspect the sequence to find a pattern.

So if we sum all those layers together, we get...

Where D is the number of diamonds, and L is the layer of interest. So given that that previous layer must be complete before we start our own layer, we can subtract away everything from the layer below our own, and are left with N-D diamonds.

Now I'd reform the question as follows... how many of the remaining diamonds would have to fall on the opposite side from ours for the layer not to complete up to our location? Well, our location at height Y means that there would have to be at least Y diamonds falling on our side for us to get a diamond. That means that if only Y-1 diamonds fell to our side, N-D-(Y-1) diamonds must fall to the other side. If this number is greater than the other side can hold, then there is a 100% chance that our location will get a diamond. If N-D < Y-1, then there is a 0% chance that our location will get a diamond.

A quick google search tells me...

"

The general formula for the probability of w wins out of n trials, where the probability of each win is p, is combin(n,w) × pw × (1-p)(n-w) = [n!/(w! × (n-w)!] × pw × (1-p)(n-w)"

Since the probability p = 0.5 (its equally likely to fall left or right), and we want to consider all cases from Y to N-D, we can reformulate as follows...

So we've arrived at a formula for calculating the probability. I haven't checked my numbers, since I didn't actually reach this part in competition, but I'm fairly certain that it will work. Another optimization in implementing this summation is to recognize that as w gets larger, the added probability gets smaller. We probably can stop the search early if the probability of the last iteration times the remaining iterations is less than the threshold google checks for... In cases where N-D is quite large relative to Y, this can be very useful.

Problem Garbled Email:

Gagan just got an email from her friend Jorge. The email contains important information, but unfortunately it was corrupted when it was sent: all of the spaces are missing, and after the removal of the spaces, some of the letters have been changed to other letters! All Gagan has now is a string S of lower-case characters.

You know that the email was originally made out of words from the dictionary described below. You also know the letters were changed after the spaces were removed, and that the difference between the indices of any two letter changes is not less than 5. So for example, the string "code jam" could have become "codejam", "dodejbm", "zodejan" or "cidejab", but not "kodezam" (because the distance between the indices of the "k" change and the "z" change is only 4).

What is the minimum number of letters that could have been changed?

My Solution:

This was the problem I actually attempted... and while I produced valid results for the small example test cases, it was far too slow to actually finish even the small dataset. Funny, I work at an email company, and have a coworker named Jorge... I couldn't resist trying this problem instead of the second. I'll present my ideas here, but would be interested in seeing what the correct approach is to this problem from someone else. It reminded me of a problem I'd done on my blog a few months ago... a Morse Decoder... so I felt like I could reuse some of those ideas. The wildcard matching needed seemed to make this problem much harder... so I went about setting up the dictionary in a tree, where each node of the tree contains a dictionary mapping the next character to the list of possible nodes, as well as a list of all sub nodes. When inserting the dictionary into this tree, I broke it up into N trees, where each tree was of words of length n. The tree class then had a function for returning the distance between itself and a given substring from the test case... that code looked like this:

Here, scoreSoFar is initialized to 0, and bestSoFar would be the length of the word (where we would have to change all letters to match something in the dictionary). Then this code was used in a recursive search, where we'd map out all possible first word fits in the test case, and recursively search the remaining part, keeping the minimum score of that. I tried caching as I went for reuse, but that didn't really help. This was just way too slow. Interested in feedback on successful solutions.

So those are my thoughts on Round 1B of the code jam. Last chance for me is 1C... if I can stay awake that late.

So those are my thoughts on Round 1B of the code jam. Last chance for me is 1C... if I can stay awake that late.